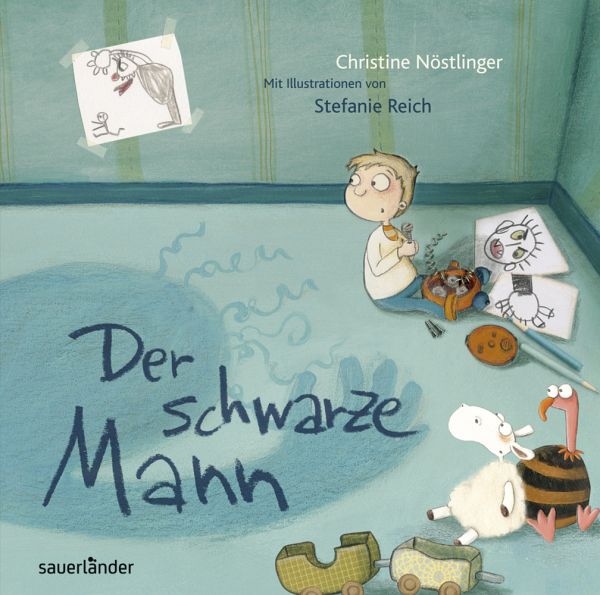

Christine Nöstlinger's Bogeyman in her children's book 'Der schwarze Mann' (the Black Man)

Who is the author Christine Nöstlinger?

She was born in Austria in 1936 and died at the age of 81. Nöstlinger is the holder of many prestigious prizes and has been commended for her contribution to children's literature in the broadest sense. She is the author of more than 100 children and young adult books and her works have been translated into nearly thirty languages. Some of her more well-known books include Fiery Federica (1975), originally published in German in 1970, The Cucumber King, first published in 1972, Fly Away Home, originally published in 1973, The Factory Made Boy, published in English in 1976, one year after the original publication.

Wartime, a socialist family in a working-class background, the fight against oppression and for more social justice all figure in her books. Not unsurprisingly, she has been compared to Astrid Lindgren, the famous creator of Pippi Longstocking and both authors reveal an anti-authoritarian streak, using fantasy and humor to criticise and parody their immediate social and historical context.

In one of her acceptance speeches (for the Hans Christian Andersen Award), she lays out her recipe for children's books when she started writing and what she aspired to - she believed that children were not encouraged to create Utopias for themselves and took it upon herself to show children just how humane, just and beautiful this world could be. Once exposed to this better world, she hoped children would be motivated to contribute to its materialisation. To this end, her child characters are not well-behaved conformists but defiant, rebellious, cheeky, curious kids. Such a premise for writing children's stories is highly laudable and a critical gaze that is both humourously scornful and disrespectful of authority is still very much needed, especially in societies where social injustice, fear and ignorance prevail.

In recent years, Nöstlinger's books have also drawn some scrutiny for its politically incorrect words such as nigger, a term that was earlier widely used and which appears in Otfried Preußler's and Astrid Lindgren's children's books as well. A sign of its historical context or an indication of much-needed updates or revisions to reflect a changed post-colonial world`? When asked about the 'armen Negerkindern' (the poor nigger children') in her 'King Cucumber' book and how she felt about the inclusion of footnotes that contextualised such terms and corrected them to 'black children' instead, Nöstlinger was dismissive ('eigentlich ist es mir gleich' - - 'I don't care much'). She does agree, though, that inserting such a commentary may encourage some critical thinking but seems wary as to its actual capacity to bring about change - first create consciousness and awareness and that will be reflected in the words, not vice versa, she argues. In an interview with Ute Wegmann, she recounts her grandfather's first encounter with a Black US soldier and his wonder at seeing a 'moor' for the first time. This was the reality back then and that is how she wants to critically retell it. Within this backdrop, the 'Black Man' in the title of her book is both a provocation and a reflection of colonial racism embedded in the language.

The Black Man, recommended for ages four and up

Who is the 'black man' in the title of the story? He is the bogeyman Anton's mother uses to scare him when he has done something she isn't happy about: 'Once upon a time, there was a little boy called Anton. Anton was not a very obedient child. And each time, when his mother was annoyed, she would threaten him - 'Anton, if you are naughty, the 'black man'/bogeyman will come and get you.' The constant threat of the black bogeyman hovers over Anton until one day, his imagination runs wild and he gives the black bogeyman a form and body of his own creation. Instead of the image his mother threatens him with (he draws pictures of the black man with enormous hands, bristle hair, a burning read face, vampire teeth and a devil's tongue), he confronts his fear and indeed, the bogeyman becomes his friend, guiding him, helping him, accompanying him when he is alone in his room with his bowl of cabbage soup - Anton's bogeyman friend was very old and scruffy and no bigger than an umbrella. He had grey hair with ringlets and a crinkled face. He was toothless with glassy blue eyes. In order for Anton to be friends with this scary black bogeyman, he first has to 'whiten' him a little, creating a helpless, toothless, blue-eyed figure!

In fact, the clever Anton turns the bogeyman on his mother and rears his ugly head when she interrupts them in his room. Anton's mother becomes so scared that she promises never to mention the bogeyman again and with this, Anton puts him away too. So who is the bogeyman? He is a figment of Anton's imagination. The little boy uses his mother's threats against her and becomes the bogeyman she constantly threatens him with.

Nöstlinger is interested in exploring the abuse of authority, the habit of instilling fear in children to pull them up and the negative effects they can have in the child-parent relationship. In fact, the 'black man', this catchy title of her book, is simply the artifice she uses to empower the child.

Not long before her death in 2018, she had announced she would not be writing any more books - 'everything is so different now, I don't understand the world anymore'. Indeed, the world we live in today is quite different from the one she imagined and Black people are real, not just fictitious bogeymen, used to scare children into good behavior! Bold, derisive and even revolutionary in her times, I argue that the use of the 'black man' in her children's book is embarrassing and offensive. As an authority in the German language and a well-respected and loved writer whose books have been widely translated, her responsibility is enormous and Black parents would (rightly) cringe at this figure.

Nöstlinger's 'Der schwarze Mann' sadly reinforces dominant prejudices about Black people being mysterious, ugly, scary and bad. With all the hate and racism rearing their ugly heads everywhere, we could do with more books normalising different skin colours and fewer that ostracise the Other and demonise Black people, even though this is by no means the intention of the author.

In libraries where it is already quite difficult to find books featuring positive stories about integration and protagonists who are not dominantly white, blond and blue-eyed, books such as 'The Black Man' are indeed distressing and irritating!!