More and more

picture books that deal with war, fleeing and coping in a new society are

popping up in our bookstores and libraries. What images are children being exposed to? Who

are the writers and what aspects of fleeing and resettling are being brought into

focus? What role do (skin) colour and language play? Do the picture books

foster a greater understanding and compassion towards refugees and migrants? What

kind of voice are the ‘newcomers’ being given? Do they have leading roles in

the stories? These and other questions will be considered in this series focusing

on migration and arrival/settling in an adopted culture.

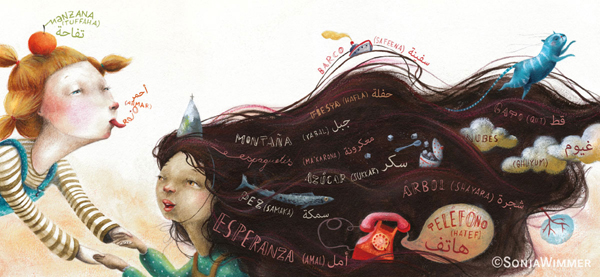

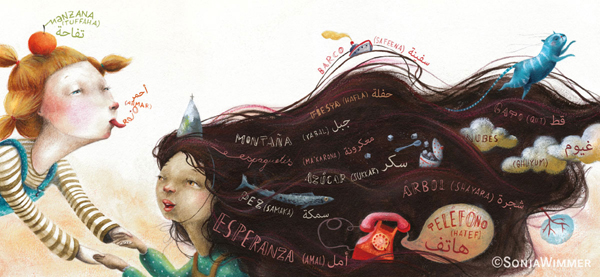

‘The

Day Saída arrived’/’Am Tag, als Saída zu uns kam’ (original in Spanish,

published in 2012), written by Susana Gómez Redondo and

illustrated by Sonja Wimmer.

The book

has been tagged/classified under the heading ‘Other Cultures’ and is recommended

for ages five and up. I had access to the German translation which I found at

the public library.

The nameless first-person protagonist is drawn to the newcomer Saida and her silence. She tries to find out why the girl doesn't speak, until her parents finally explain that this little Moroccan is probably shy and insecure because her language is different. This is the start of a quest to teach Saida her language and learn Arabic at the same time; it is the beginning of a friendship that deepens as both girls learn each other's language and dream of a world without borders.

In the following paragraphs, I will closely look at some of the text and illustrations in order to point out the following:

-The book is really about the blond, blue-eyed girl and the journey she embarks on when she befriends Saida.

-It presents an outdated representation of both 'Spain' and 'Morocco' (white vs black; civilised vs medieval) and ignores the centuries-long proximity and interaction between the two countries.

-Very few Moroccans would relate to the stereotypical images of palm tress, mint tea and deserts that are used to represent their country. In fact, as we will see, that's about all we learn of Morocco!

- Morocco and its languages are oversimplified which further distances the reader from all the similarities between both countries, separated by merely 14km and with deep ties, whether acknowledged or not! In fact, in the north of Morocco, Spanish is widely spoken and used!

In this book, the author attempts to bring people together through language. Both protagonist and newcomer are enthusiastic about each other's language and a friendship develops. Language helps to break down barriers, demystify cultures and put people on an equal footing. This is especially important since newcomers with a different language often feel inferior or are made to feel so. This book promotes a sharing and mutual respect and learning that are key to integrating newcomers in a host society.

The book's message, however, is stifled by the lack of a more active presence of Saida - (with the exception of the first page, it is only towards the middle of the story that we finally see illustrations of her). It is the protagonist's mother and father who explain who she is and why she can't speak. That is to say, there is little interaction between both characters that would create sympathy and closeness to the newcomer Saida. The extremely limiting and stereotypical images associated with Saida - mint tea, deserts, camels, palm tress - really tell us nothing about Saida and prevent her from becoming a full character. Thus, the reader has to rely on the illustrations to flesh out who this girl is. The black fuzzy flowing hair makes her seem more unreal than real, reinforcing the distance between the reader and this girl with her little suitcase. It takes more than language to get rid of borders. Borders are sometimes embedded in the language and illustrations themselves!

Following is a closer look at some of the illustrations and text:

The day Saída arrived – From the start, we expect to find out about Saída through her contact with the protagonist, a blond, blue-eyed nameless

girl whose mission is to get Saída to speak and break the ice

between them. The first illustration is potent; the long dark hair of the

dark-skinned girl with a tear rolling down her cheek and the protagonist on her

ladder, opening drawers in Saída’s head, trying to find her way

around this mysterious, silent, sad figure, who seemed to have lost her speech.

The little blond girl continues her absurd quest to find Saída’s lost words in the following page where Saída herself is

absent (Am Tag, als Saída zu uns kam, suchte ich unter den

Tischen, der Tafel und den Pulten. Ich sah in den Heften nach und

zwischen den Buntstiften. Unter

den Kissen und in den Büchern. In den Manteltaschen. Hinter den Vorhängen,

den Zeigern der Uhr und zwischen den Buchstaben der Geschichten .– The day Saida arrived, I looked

under the tables, the blackboard, the desks. I looked in the notebooks and in

between the coloured pencils, under the cushions and the books, in the coat pocket,

behind the curtains, the hands of the clock and in the letters of the stories.)

In the

third page of the book, still no Saída, but the protagonist’s mother,

her eyes covered by mist, holding a cup of coffee. On the fourth page (Am Tag,

als Saida zu uns kam, wusste ich sofort, dass ich sie immer gernhaben würde –

the day Saida arrived, I immediately knew I would always like her), the protagonist

draws a welcoming heart for Saida in the snow and Saida’s sad blurry

reflection is shown.

Already the

fifth page and still no meaningful presence of Saida, only the little blond

protagonist looking up into a statue’s mouth, still in search of Saída’s voice and words. In the following page, the sixth, we are finally

introduced to Saída..through the explanations of the

blond girl’s mother – Am Tag, als Saida zu uns kam, erzählte Mama mir von einem

Land voller Wüsten und Palmen. Mit dem Finger zeigte sie mir auf dem

Globus Saidas Heimat. Marokko stand darauf und ich sah, dass es gar nicht so

weit weg war- the day Saida arrived, my mother told me about a country full of deserts and palm trees. She pointed out Saida's country on the globe - Morocco, and I saw that it wasn't very far away). As if that’s not

enough, the father then continues to explain to the protagonist who the girl is

and why she can’t speak – she probably hasn’t lost her words, explains the father,

but is too shy to speak them because they are different from ours. In Morocco,

he continues, you would also not be understood if you were to use your language. Corresponding to this text, Saida is pictured with her whirlwind

hair and a suitcase, with Arabic letters behind her and a setting as empty and

arid as a desert.

Again, in

the seventh page, it’s a close-up of the blond protagonist and her finger shadows of

a camel that are seen. She discovers that in Saida’s country, the language is

Arabic and she has decided to help Saida learn her language. That’s not all,

she wants to learn Saida’s language too. Her reason for learning Saida’s

language? – so that she would be understood when she travels to Morocco.

In the next

page, we see an illustration of both girls, on a hippopotamus, exchanging words

in their respective languages. Their relationship blossoms as they discover each other’s

language.

From now

on, the illustrations often show both girls together, one blond, the other very

dark-skinned, with wild dark, frizzy hair in a whirlwind. Their friendship continues

to deepen and Saida’s image becomes even more surreal and magical, almost like

the desert she is supposed to represent. In her long flowing black hair, words

and images are drawn, on her head stands a tiny hat with a cross! This illustration

has little to do with the text itself – the girls laugh at each other’s

inability to pronounce some sounds and they exchange sweets after their

laughing fits – the nameless blond protagonist offers her a slice of cake while

Saída gives her friend a sweet made of almond and honey.

In the

following page, Saida, with her black, magic-like tornado hair is pictured on a

tree - she has been in her new country for some time now (this is shown in the illustrations through the changing seasons) and Saida’s voice (I imagine in Spanish) is now full, loud and

clear - you can hear her laugh and her hair blows freely in the wind.

In the

second to last page, Saida is sensually pictured in a tent with a camel on wheels

in the background and a teapot next to her, while the protagonist is decked in

an oversized turban. They now make fun of each other’s pronunciation and partake

of each other’s ‘culture’ – (couscous and lentil soup, the story of Alladin

and a nursery rhyme). Someday

they will both visit Saida’s country (with its palms, camels and deserts) in

a ship or a flying carpet. On the way, they will look for more words that make

people laugh, talk and build friendships. They will then, finally, both throw

the word ‘border’ overboard! In this last page, they are pictured flying on a

carpet with Saida’s tornado hair, blowing in the wind - a symbol that she is

finally free, thanks to the blue-eyed, blond protagonist.

At the core

of the book is the following message – In each language, there are reassuring

words and hateful words; words that unite and others that divide, words that

hurt and others that make you laugh. Language has the power and beauty to bring

people closer together. It’s a story about an

unnamed protagonist who wants to befriend Saída and help her

with the language of her new culture. This is the start to a deep friendship

where the protagonist is not only interested in teaching Saida but also in

learning about Saidas language and culture. Their magical journey helps them

imagine a land where borders don’t exist.

As already mentioned, this message becomes ineffective because of the illustrations and a very belittling, embarrassing representation of Saida and her country. We get to learn and visualise her language through the illustrations but it takes much more than this to bring people closer together and get past very real borders.

In the following commentary, I will introduce a very similar book about friendship and language between two girls and point out some significant differences which allow for a more balanced representation of the newcomer and her efforts and pains to find her place in a different country.

My two blankets by Irena Kobald and Freya Blackwood, recommended for ages five and up.

A little girl (only known as Cartwheel) leaves her country with her Auntie because of the war. Everything is strange in the new country - the people, food, animals and plants...and of course, the language (nobody spoke like I did). It makes her feel alone, 'like I wasn't me anymore'. At home, she wraps herself in the warm blanket of her own words and sounds which makes her feel safe and comfortable.

A girl in the park waves to her one day but she is too shy and scared to wave back. When they do meet again a friendship develops and language isn't a barrier for long. With each new visit, the girl brings her some words - 'some were hard, some easy. Sometimes I sounded funny and we laughed'. Soon the new words don't sound so strange anymore and Cartwheel starts weaving a new blanket which grows with the new words she adds to it every day, until it finally feels as soft and comfortable as her old one. 'No matter which blanket I use, I will always be me'.

There is a stark parallel between this story and the one discussed above 'The Day Saida arrived'. The narrative perspectives chosen significantly alter the reader's identification with the characters. In Saida, the reader identifies with the nameless blond protagonist while in 'My two Blankets', the newcomer's emotions of sadness and confusion are more closely felt. In this book, we do not know the name of Cartwheel's country and the author makes no attempt to bring the reader closer to her past. Nonetheless, what is important and stressed in the story is the 'old me' that the protagonist can hold on to and seek comfort in when she is sad or alone. Furthermore, a 'new me' slowly emerges as the protagonist deepens her friendship and learns the language. She is now comfortable with both identities and therefore, in her own skin.

Both books emphasise the importance of learning the adoptive language to assimilate to the new country and culture. What is missing, however, is a meaningful exchange. The child protagonists have to assimilate to fit in and are physically and culturally different which are indirectly seen as obstacles. They are dependent on the benevolence of the native (blond, blue-eyed) to access the language and feel welcomed. The welcoming country's self-image has therefore not changed per se; it has absorbed difference, all the while failing to recognise the wealth in diversity.

Meine liebsten Dinge müssen mit (My favorite things are coming with me) by Sepideh Sarihi, illustrated by Julie Völk, recommended for ages five and up.

A little girl's world is suddenly turned upside down when her father announces they are moving to another country. She is given a little suitcase and asked to pack only her dearest things. But how can she pack her aquarium, a pear tree, a wooden chair from her grandpa, the bus driver or her best friend? Facing the sea, also one of her favourite things, she manages to overcome her sadness and face the challenges migration presents. The sea is everywhere - why not bottle some of her favourite things and let the sea do the rest? In her new home, she rides to the sea everyday with her bike, patiently and contentedly hoping to find the bottled pieces of her past.

An endearing book written in first person that expresses the pain and hope associated with migration. Detailed illustrations that complement the simple, sparse text; the exclusion of specific names of characters or places allow the story to easily traverse borders. There is no reason given for leaving their country - the reader just knows that the parents are quite happy to leave. In fact, the immediate circumstances become irrelevant and the girl's emotions invite the reader to share her dislocation and sadness which are turned into creativity and hopefulness.

A very engaging, effective story to start a discussion about what it means to move to another country, the reasons, the journey, challenges in the welcoming country, etc.

Marwan's Journey (originally in Spanish, El Camino de Marwan) by Patricia de Arias, recommended for ages five and up

Finding hope not in the adoptive country but in rebuilding the rubble:

A little boy is forced to take big steps, many steps and he is carrying a heavy load - the burden of his family, of his town and his country; his story is their story. His destination and arrival are unknown, His mother's voice, which he hears in his dreams, urges him to continue going, to not look back. He recalls the warmth and comfort of his home and family and the night everything suddenly changed. His feet and fate are linked to hundreds of others fleeing to safety.

What is uncertain is why this little boy is alone on his journey - did his parents die along the way? Were they killed in their homes? He reaches a border where there is another life, another home, another language but dreams of returning home to rebuild what he has lost.

A lyrical, cyclical story which pays homage of sorts to those fleeing, uncertain of whether they will make it or not, torn by their loss and separation and hopeful of a new beginning, not one in the adoptive country, but the one they left behind in ruins. And this is where, in my opinion, this story stands out - it doesn't really create sympathy for the character Marwan - his story is too ambiguous, tirelessly repeated in the picture books. But this hope in returning to rebuild a country they are forced to leave, hope that there will be peace once more and that the protagonist will be a part of it..looking forward to be able to go back one day, forever - is what the reader is left with in the end.

'Wasims Weste' (Wasim's Waistcoat) by Anja Offermann and Christiane Tilly, recommended for ages five and up

Published in 2017, this picture book is part of a series under the heading 'Explaining Fleeing and Trauma to Kids' that seek to sensitise children and readers about the growing number of refugees especially from Syria and their journeys and fate once they make it, in this case, to Germany.

This is what Wasim's journey looks like -war breaks out in his town and he and his family begin their flight to safety - a bus takes them away from the town, a small boat takes them over the waters before they are rescued by a ship. They walk for several days and then board a train before they arrive in an unknown place in Germany where they are housed in a shelter.

Wasim's grandparents stay behind and at the shelter in Germany, they meet other newcomers from their town and country who describe the worsening situation.

Wasim's family receives help - clothes, German classes, etc - and slowly tries to make themselves useful in their new country - Wasim's father is a hairdresser and his mother takes up sewing jobs from the people in the centre. There is the prospect of hope as the family plans to move to a flat and Wasim looks forward to starting school.

The inside cover of the book presents a carthographic representation of Wasim's journey. We are presented with a traditional Muslim family and the trauma and hope they bring with them as they try to start a new life, free from war and fear. The title refers to the waistcoast given to Wasim by his grandmother, a present that will protect him on his new and unknown journey in search of peace and a new home.

Once in Germany, the characters struggle to overcome the fear and trauma that continue to besiege them. Music, drawing, games and personal support help them deal with their harrowing experiences.

While this book creates sensitivity towards refugees and migrants fleeing from war and crises, there is still little (or no) interaction with the wider society. Wasim's story is just beginning and his experience once he gets out of the shelter will be challenging. While the book provides summarised information about the journey and fate of refugees fleeing the war in Syria, there is little about Wasim's character that endears him to the children reading/watching this book. Wasim is simply this 'other' boy with a family who is looking for peace and a new start.

Below, I will look at two more books that deal with the topic of war, fleeing and settling in a new country. 'Neues Zuhause gesucht' and 'My name is not refugee' also recreate the journey of fleeing and all the hardships it entails. In the first book, the author employs a group of penguins who are forced to find a new home. In the second, 'My Name is not Refugee', the author successfully manages to create more sympathy and closeness to the child character. We will look at how this is achieved.

'Neues Zuhause gesucht' (In search of a new home) by John Chambers and Henrike Wilson, recommended for ages 4 and up.

'Jeder hat seine Geschichte...Aber manche Geschichten lassen sich schwer erzählen. Und manche Entscheidungen sind schwere Entscheidungen' (Everyone has a story...but many stories are difficult to tell and many decisions difficult to make)

This front cover of a group of scared, wide-eyed penguins in search of a new home does not help us to connect with the plight of the animals. In fact, such a picture can be interpreted as threatening and indeed, when the penguins do arrive in a safe place, not all of them are allowed to stay. The little penguin with the red scarf, lost among the other penguins, is the protagonist and takes us through their perilous journey before reaching safe shores. Unlike 'Wasim's Waistcoat', discussed above, this story establishes contact between the newcomer and those already settled and the initial distrust and fear towards the group of penguins. However, it fails to create sympathy towards the plight of the penguins and simply reflects the dilemma of refugees without transcending this reality or creatively reworking the arrival of these newcomers. The use of animal figures certainly helps to establish some distance from the reality of the crisis. Yet, the potency of these images are not exploited to bring the reader closer to the plight of those fleeing war and conflict.

The penguins' world is turned upside down by war (The war was big like the sea and loud like a storm) and they all flee in a small boat (never mind penguins can swim and are at home in the water), scared and bundled together. They are rescued by a whale and brought to shore. Everything is strange. Up to this point, the illustrations feature the penguins in a large group and this prevents the reader from connecting to their individual desolation. Large groups are associated with strength and they can also appear intimidating, if not threatening. Furthermore, the protagonist's voice is lost in this multitude and there is nothing that singles her/him out for the reader to identify with or connect to.

The other animals stare at the newcomers with a mixture of fear, distrust and surprise. In this multitude, one little racoon stands out. The little animals play with each other and a bunny is now wearing the penguin's scarf. They teach each other new games and become friends. Even the adults get to know each other A LITTLE better. BUT not everyone wants to or is able to stay. Our new home is different, notes the little penguin, but 'we are now here and that is my story'.

Let us now look at

'My Name is not Refugee' by Kate Milner (recommended for ages 3 and up) and see how the author treats the question of war, flight and arrival.

The title alone is arresting and forces the reader to confront his/her prejudices and the current discourses on migration, for every person leaving their home has a valid story to tell and real emotions that should not get lost or drowned in the sea they are sometimes forced to cross.

One of the strengths of this book is the inclusion of thought bubbles, engaging the reader to put herself in the shoes of the little character - for eg. Do you think you could live in a place where there is no water in the taps and no one to pick up the rubbish; How far could you walk?; What is the weirdest food you have ever eaten?, etc.

The inside of the front and back covers are filled with a sea of tents and this book tries to give a face and voice to its dwellers.

A mother tells her child - 'we have to leave this town, it's not safe for us. Shall l tell you what it would be like?' And so, she prepares her child for the journey they are going to embark on:

'We'll march and dance and skate

and run and walk and walk and walk

and wait and wait and wait

and get up again and walk and walk'

...'we'll get to a place where we are safe and we can unpack'

...'and soon those strange words will start to make sense.

You'll be called Refugee but remember Refugee is not your name'.

The mother takes her child on this imaginary journey that is about to become real and the reader joins in, feeling what the little boy might feel. A journey is exciting but also scary with lots of obstacles along the way. At some point, you arrive and unpack and later on, the strange sounds become familiar and you are forced to find your place in your new home. 'Refugee is not your name' - with your new, learned voice, there will be a responsibility to tell people your 'refugee' story.

The book is aimed at explaining to its middle-class readers what it might feel like if you are suddenly wrenched away from your comfort zone and forced to find a new home. It is engaging and offers lots of space to discuss migration, war and moving to another country. The illustrations - with difficult scenes (border, sleeping in tents) and exciting ones (walking, meeting other kids and making friends) further offer a complementary space to discuss migration without distinguishing the characters along the lines of race, religion, culture etc. 'Unlike Wasim's Waistcoat' or 'In search of a new home', this picture book effectively manages to give a face and voice to the term 'refugee'.

In the next commentary, I will also take a closer look at another touching story '

The Day War Came' by Nicola Davies who uses her anger and strong voice to protest against the British government's decision to not allow 3,000 unaccompanied child refugees from Syria into the country.

The Day War Came, by Nicola Davies, recommended for ages 5 and up

Before I take a closer look at the book itself, I would like to quote its author on showing solidarity in times of war and on the message of her book:

'

The story of refugees is the story of our species. Tomorrow, you and me, our kids, our grandchildren could be the ones fleeing for our lives with our babies on our backs and the wrong kind of shoes on our feet. So it's time we changed our attitudes to accommodate this reality'

'The message is so simple, as simple as an empty chair - we need to be kind, we need to share. Because we could be next. Because every person matters. Because that's what makes us truly human'

(from booktrust.org.uk)

This poem, first published in the Guardian before being turned into a picture book illustrated by Rebecca Cobb, is also partly inspired by a story its writer heard about a child refugee whose camp was close to a school. One day, she entered and was turned away by the teacher who said there were no empty chair or desk for her to sit at. The next day she returned, with her own make-shift chair and asked, 'Now, can I come in?`. It is inspired by the war in Syria and the multitude of child refugees it has spawned and the welcoming countries' reactions to plights for help.

Davies creates a context for the unnamed child protagonist who is sitting at her desk at school learning about volcanoes and tadpoles when the war bursts in, destroying everything in its path. But even before this, it is a beautiful home setting of normalcy and comfort that introduces us to the character - 'The day war came, there were flowers on the windowsill and my father sang my baby brother back to sleep. My mother made my breakfast, kissed my nose...'

All that is left of her home after the war is a blackened hole and their journey to a safe land is long and arduous. But she soon finds out that the war has followed them - 'it was underneath my skin, behind my eyes and in my dreams'. The war was not only in her, but all around her too - 'But war was in the way that doors shut when I came down the street. It was in the way the people didn't smile and turned away'.

She sees a school and enters but is turned away by the teacher who says there is no empty chair. War had also got there too, it seems. But when all seems lost, a child appears with a chair for her to sit on. That's not all, more children bring more chairs for the other refugee children. The road was now lined with chairs and they walked, defeating the war with every step.

This is a story about the struggle to remain human in the face of calamities; it is hope in the generation of our children to want for the other what we take for granted - peace, a home, an education. When war breaks out in one part, it affects us all. We are also at war when we reject others, especially children, in need of safety and shelter. Davies emphasises this human aspect, putting everything else - skin colour, cultural differences, 'the boat is too full' mentality, aside.

A heart-warming book that makes you want to draw an empty chair too.